Scottish football boasts some of the fiercest rivalries, greatest banter and proportionally highest crowd numbers in the world. It is a whirlwind of colour, passion, angst, joy and camaraderie. In a footballing landscape that is polarising the über-wealthy from the rest; it retains a wonderful authenticity that sticks fairly close to what the game used to be all about.

I’m reminded at this point about a conversation had with the very excellent sports writer John Nicholson (@JohnnyTheNic). On finding out he resided in Fife, I’d expressed dismay that I used to enjoy his writing and asked him to at least confirm he isn’t a Dunfermline supporter. He replied “Of course not, I’m no glory hunter”.

While the nearby Premiership has become a caricature of itself, churning money and losing its identity and connection with the fans, Scottish football has more or less retained its charms. The chase for ever more wealth is not as desperate to those who can accept that the football club exists to give their supporters something to cheer about, something to enjoy at the weekend and to service the community they represent. That is something to be proud of. You would hope that it also would breed governing authorities that take on board that ethos and deliver a product that is tailored to the real stakeholders in the game – those communities up and down the country that really care about the game. You would be wrong.

In this series of articles we’ll look at Scottish football, its regulators, what is really important and a damage report all through the prism of the biggest crisis Scottish football has faced in living memory. An event that continues to affect opinions, cause massive reactions and counter-reactions and stigmatise large sections of Scottish football. The 2012 collapse of its most decorated club.

Part 1: Too Big To Fail

The collapse of Rangers in 2012 caused a crisis in Scottish football, the reverberations of which are still being felt today. To many fans this is almost the point at which the clocks stopped and no cohesive best-for-all way forward was possible any longer. So we will start our examination of this with the conditions that allowed it to happen.

The phrase ‘too big to fail’ has its roots in the 2008 banking crisis and that is apposite for two reasons. Firstly, because it too has a regulator and the crisis was largely seen as a failure to provide effective regulation. Secondly, because it came several years before the events we will discuss so there was ample opportunity to see the similarities and take appropriate action.

In 2010 (again well before the crisis in Scottish football), Federal Reserve Chair Ben Bernanke had set out several risks with ‘too-big-to-fail’ institutions:

- Such firms create “moral hazard” – “If creditors believe that an institution will not be allowed to fail, they will not demand as much compensation for risks as they otherwise would, thus weakening market discipline; nor will they invest as many resources in monitoring the firm’s risk-taking. As a result, too-big-to-fail firms will tend to take more risk than desirable, in the expectation that they will receive assistance if their bets go bad.”

- It creates an uneven playing field – “This unfair competition, together with the incentive to grow that too-big-to-fail provides, increases risk and artificially raises the market share of too-big-to-fail firms, to the detriment of economic efficiency as well as financial stability.”

- Such firms become major risks to overall financial stability – The failure of … large, complex firms significantly worsened the crisis and the recession by disrupting financial markets, impeding credit flows, inducing sharp declines in asset prices, and hurting confidence. The failures of smaller, less interconnected firms, though certainly of significant concern, have not had substantial effects on the stability of the financial system as a whole.”

Hopefully it can be seen the parallels with Scotland’s biggest football clubs. The financial models build around them – especially media rights – affect all Scottish football infrastructures as money from the rights trickle down the pyramid. When Rangers hit severe financial difficulties, it posed an existential threat to the viability of many in Scottish football. In the banking sphere, there were four main solutions offered to how to counteract such risks:

- Break up the largest: Pretty unpalatable to fans of Scottish footballs biggest teams.

- Reduce risk taking through regulation: A distinct possibility and indeed what Financial Fair Play (‘FFP’) seeks to do.

- A too-big-to-fail-tax: This would involve the biggest clubs being limited by penal taxes as they grow beyond a certain size and would impair competitiveness to clubs in other countries artificially. Unless systematically adopted it’d be akin to shooting our clubs in the foot in Europe.

- Monitoring: Essentially keeping a particular eye out on those that are considered the highest risk of causing systematic failure.

If you were to look to these as a starting point for how a comparable risk issue in Scottish football might be handled, you’d probably only really see items 2 and 4 as being workable or acceptable in Scotland in isolation. They can work in tandem.

Regulation to manage risk

As regards a regulatory response, the most obvious would be to set limits within which clubs can operate freely with automatic notifications when any breach occurs. What those parameters might be are open to debate, but it would seem likely that factors that influence risk include liquidity, anticipated cash flow shortages, contingent liabilities or provisions of a certain size, levels of asset cover free of security, profitability ratios over time, etc. This would then allow the regulator to strike a balance between being free to manage a club and clear guidelines on how far out the boat can be pushed. A number of studies have looked at turnover to wages ratios in football. There is a balance to be struck between spending to achieve success on the field and reap the benefits in turnover that come with that success. The studies cumulatively suggest a ballpark of 60% is around ideal in balancing these, though a particularly interesting variation includes interest alongside wages.

Monitoring

Most regulators in recent years are adopting a risk-based supervisory framework. This typically involves gearing more of the regulators resources towards those participants where risk is considered the highest. Those where failure is likely to be catastrophic are likely to get extra attention while those where it is less so, a lighter touch approach to inspection and monitoring. Additionally where there are indicators of concern the resources are adjusted accordingly also.

In most regulated industries regular (often quarterly) reporting to the regulators on statistical information is considered par for the course. In such a way football clubs could work in tandem with the regulator, providing them with regular updates on information relevant to the risks they are managing in terms of the size and risk tolerance.

Direction Within Europe

This isn’t really new in football. UEFA has already taken steps towards this in its Financial Fair Play approach. Critics would decry its effectiveness (citing Manchester City and Paris St-Germain as prime examples) but it at least recognises the problem. Football needs to be protected from itself. It cannot be permitted that clubs gamble their very existence on chasing success. Responsible stewardship is needed. If it can become effective it can be a very useful tool in ensuring clubs are run responsibly and sustainably.

The UEFA club licensing system is also a step in the right direction. It started out in 2004 as an endeavour to raise minimum standards of governance at football clubs to prevent mismanagement and ruin. Exactly what was needed in Scottish football at that time. It is now going beyond that to ensure elements like fan safety and facilities and ensuring appropriate levels of management and organisation within clubs. It began intended to be applied to clubs participating in UEFA competitions but the idea has spread to national associations including Scotland.

Direction Within the UK

In Scotland the UEFA club licensing system has been embraced. Credit to the SFA on this – they’ve introduced a level of national club licensing on top of that required for UEFA purposes. It also does help re-engage the club with its supporters and other stakeholders by representing some of their interests. It includes financial elements. But it is not regulation and it is not ongoing regular monitoring – it is done annually. It could certainly be expanded to encompass this.

To compete in the SPL or Championship just now clubs require to have at minimum a Silver or Gold license (Platinum is given exceptionally to those exceeding the gold standard). To provide examples the following table provides details of the current ‘Gold’ standard when it comes to financial elements:

| (i) The auditor’s report in respect of the annual financial statements shall not include an emphasis of matter or a qualified opinion/conclusion in respect of going concern….

(ii) Where the annual financial statements disclose a net liabilities position, a club cannot meet the Gold criterion. |

Neither of these are prerequisites for a Silver member. In respect of (ii) it can meet Silver if it meets the conditions the Licensing Committee set in its own discretion. |

| … a club or any parent company of the club included in its reporting perimeter cannot have been subject to an Insolvency Event as defined in the Scottish FA’s Articles within the period between 1 June 2018 and the licensing decision in the calendar year 2019. | Does not actually proactively seek to prevent such events – just deal with the immediate aftermath of a recent insolvency event. |

And that’s pretty much it for financial controls. Well short of effective regulation and solely reliant upon an auditors report that warns of impending disaster within the foreseeable future (normally viewed as 12 months from the date of the audit report). There is nothing that covers medium or long-term viability. Auditors are also reporting primarily to the shareholders of the club not the SFA and they do not even require any specific representation from the auditors to help ensure governance (regularly done in Financial Services legislation and regulation). Seems very much like a box ticking exercise to say something has been done doesn’t it? The UEFA standard is higher and includes forecasts etc.

The problem with UEFA breakeven requirements etc is that its meant for much bigger clubs than constitute most of Scotland. There is a very real case to be made for a domestic equivalent meaningful to Scottish clubs to promote stability. The English Championship can be looked to for inspiration here.

Other early warning systems can be implemented by agreement. E.g requirements to notify if falling behind in taxes, national insurance contributions, payment of players wages etc that would shoot clubs up the Risk-Based Assessment and trigger tighter monitoring and control by a team of auditors of expenditures to get back into a ‘safe zone’.

Even elsewhere in the UK, attitudes are changing towards management of risks. In England and Wales there is now a Code of Sporting Governance that sporting organisations requiring Westminster funding must comply with. Its requirements include:

| Risk Management and Internal Control (Requirements 5.7–5.8) |

| 5.7 The organisation shall maintain robust risk management and internal control systems.

The Board is responsible for determining the nature and extent of the principal risks that it is willing to take in achieving its strategic objectives. The board should ensure there are processes to: • consider and maintain a record of identified risks; • agree appropriate steps in order to mitigate their potential impact; • monitor and review the risk management systems; and • focus on those risks which could threaten the organisation’s financial position, strategic objectives and future performance. The board should describe in their annual report the principal risks and how they are being managed and mitigated. Risks may include financial, operational, reputational, behavioural or external risks. |

| 5.8 The Board shall conduct an annual review of the effectiveness of the organisation’s risk management and internal control systems to ensure that they provide reasonable assurance.

Although the design of risk management and internal control procedures will be influenced by the type, size and complexity of the organisation, the board should monitor the effectiveness of the risk framework and include this in their annual report. |

Given the drama of 2012, it would be foolish not to currently consider such a failure by a ‘too-big-to-fail’ club as being a significant risk. Despite the above (which it should be noted is not binding in Scotland) the SFA annual reports give very little away.

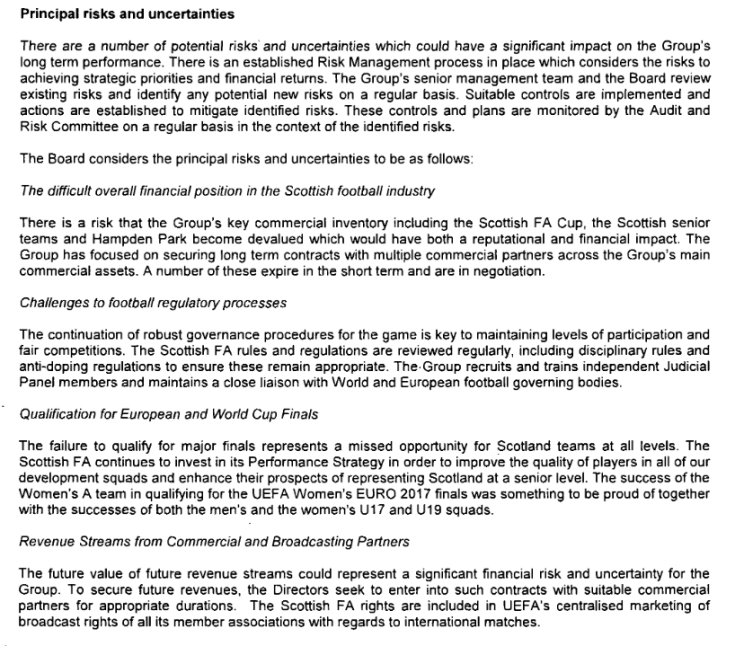

[edited 27/3/2019… From the annual financial statements of the Scottish Football Association it can be seen the ‘significant risks’ that they have identified to their own business (which really aught to correlate to Scottish football welbeing more than it does):

It certainly does not fill one with optimism that the SFA has properly considered the systemic risk of failure including catastrophic failures of those ‘too big to fail’…..end of edit]

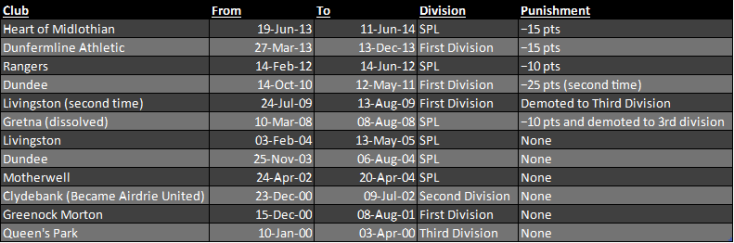

Certainly it does not appear that any great moves have been made of the sort indicated earlier. The inclusion of point deductions for entering administration were undertaken in 2004 by the league bodies – at the same time a similar change was done in the English leagues – rather than the SFA. Those penalties were stiffened in 2015. Remember though, it is the SFA who are responsible for the sporting governance and integrity, not the league bodies. This is more correctly viewed as the leagues doing something to protect themselves because the SFA had done close to nothing at all. It is also an argument for the league taking over the licensing responsibilities of the SFA for top-tier clubs.

A History of Insolvency in Scottish Football

There is a strong argument for saying that the SFA really should have been prepared when the wheels came off at Rangers. The following two tables respectively give details of the Scottish Association clubs that have become defunct (including those Liquidated when incorporated as a company) and those that have went into Administration. In the interests of brevity and context it only really includes those that have played in the league competitions under the SFA auspices and (having compiled it for this purpose) I would not attest to its completeness or accuracy.

It can be seen therefore that although Scottish football had enjoyed a period of relative financial stability in terms of insolvency events in the period since Third Lanark’s collapse, the turn of the millennium really trumpeted the start of a twelve-year period of instability.

The tables themselves do not tell the full story though. They list only the teams which circled the plug-hole or went with the bath water. There were others skirting with financial disaster in the period from the 1990’s to 2012. These included Celtic, who famously had their overdraft called in and should have been the first warning to the SFA of the ‘too big to fail’ problem that was to follow. Other old and proud clubs not in the tables but that have flirted with financial implosion – some admittedly later than 2012 – included Clyde, Stirling Albion, Stenhousemuir and Falkirk. It is notable that all these and many who survived Administration have moved towards models of fan ownership as a means to safeguard their futures. In a separate series of articles beginning here we are exploring the benefits of such models and what the SFA could be doing from that end to provide stability and stewardship to the sport.

Causes of the Financial Crisis

There are many things that can be pointed to as contributing to this period of financial malaise. They include:

- Fundamental change in the nature of football finance in the post-Bosman (1995) era where the cost of wages and transfer fees for elite level footballers built an effective European market for players and a higher turnover-to-wages ratio

- Scottish football obtains proportionately less TV revenue streams and more match day revenue as % of total turnover than most comparable European leagues and all major European leagues and during this period two such TV deals have collapsed (one when Setanta failed and another upon the demise of Rangers)

- The chasing of football success at the cost of sustained losses (burning up sources of finance) rather than a sustainable business model

- A culture of short-term decision-making and entrenched behaviour that is hard to break from

- Poor governance standards at clubs dominated by small numbers of individuals at Board level

- High comparative costs of ensuring the stadia criteria for entry to the upper echelons are met

- The fewer number of revenue generating games played as a result of the league split

- Highly concentrated ownership structures (in terms of number of shareholders) or restrictions on the transfer of shares leading to exploitation of supporter goodwill (legitimising the adoption of reckless, self-serving or irresponsible actions by leveraging the shared craving for success)

- The clubs themselves being under-capitalised and relying too much on borrowing

- There was a period (approximately 1998 up to the 2005/06 season) when Celtic and Rangers were engaged in what could be called an ‘arms race’ on wages to achieve success during which the finances of both came under pressure (one irrecoverably so)

- Latterly the banking crisis and the ensuing high costs and low availability of borrowing as well as a period of recession

What is also evident from the tables is the high level of resilience Scottish football clubs have. Perhaps partly because they are not so reliant upon media revenues so much as self-generated revenues and partly through that ability to engage meaningfully with the community to increase income in times of need; most clubs entering Administration are able to battle their way back out. A “best way forward” may very well seek to use regulation and monitoring to both limit the excesses and encourage practices that lend themselves well to this hardy resilience in times of strife.

The Rangers Situation Itself

Many of the above factors were at play in the case of Rangers. Another thing more singular to Rangers and relevant to the wages ‘arms race’ described above is the tax structuring used by Rangers. This will not be a detailed part of this series of articles. Plenty of people have written on those and what should or should not happen with titles during that period. While some of it is relevant to issues still to be discussed and will be picked up to a degree later, for these purposes it is suffice to say that it created large liabilities and so an absence of willing investors which also contributed in that particular insolvency case.

When we wrote this article on the corporate gambling that brought Rangers to the brink, the two parties identified who really share the bulk of the culpability are the old Board (chiefly Murray who dominated it) and the SFA as the regulator whose primary function it is to protect our game. Though the article focused on morality in tax planning, what fundamentally sunk Rangers in 2012 was pushing spending to the brink and over-reliance on continuation of availability of finance. These are of course very relevant to the subject of Rangers becoming ‘too big to fail’.

The focus today ought to be squarely on regulatory aspects. Though a few of the old Board are still involved in Scottish football, it is not really the overarching concern. The SFA’s risk assessment (assuming one took place) was evidently flawed with devastating consequences for the game and finances within Scottish football. The SFA and SPL/SFL role in the aftermath left many clubs – most publicly Raith Rovers and Clyde – upset with the damage limitation attempts and strong-arm approach taken. The fans of many clubs were left up in arms not only at the attempts to restrict the financial damage within the game, but also at their own clubs for adopting stances that did not reflect their own. It has led to ostensibly more support in the post 2012 period for greater fan representation within clubs according to recent fan polls.

It is telling that in the presentation given to the SFL clubs during an ill-fated 2012 campaign to insert the new Rangers into the second tier entitled “Your Game, Your Club, Your Future” that the discussion centred exclusively around the financial implications with no consideration at all into the sporting implications. It is a very short-termist view which is commensurate with the general perception that the Football authorities were ‘winging it’. In other words not only to recognise the risks and manage them – and it had been clear since 2009 that Lloyds bank had taken de facto control of the club and was seeking to reduce its exposures – but also to establish and make clear the approach it would take to circumstances which were fairly predictable, viz the liquidation of one of its flagship member clubs. There was, and remains, a perception that faced with the ‘Armageddon’ prospect of a monstrous deficit on budgets in the Scottish football world, everything else a sporting regulator is supposed to stand for was forgotten. It is a stigma that remains.

That prevention would have been better than cure was similarly never mentioned.

See No Evil, Hear No Evil

The purpose in laying out this information – for which I am thankful to readers for persevering – is to set the scene for how we got to the position that ended with Scottish football rattled to the core. Faced with a series of financial meltdowns on its watch an effective SFA would have taken proactive steps to revise its risk assessment and map the safeguards needed to manage the new circumstances. It would chart a course for its member clubs by taking a firmer hand with financial requirements and governance matters. In short it would act like a responsible regulator in looking after the industry and protecting it from lasting damage. It didn’t.

Scottish football floundered from one disaster to another rudderless and leaderless. When doing nothing didn’t help the situation, the SFA plan B was to continue doing nothing while the SPL/SFL brought in point deductions from 2004 to try to discourage financial irresponsibility.

When the worst happened and the Goliath that was Rangers came toppling down under the slingshot of Hector and the weight of debt it was barely a surprise. It would be quickly followed by Dunfermline and Hearts having close scares. Still the SFA did nothing to prevent future collapses. Even now they continue to do nothing.

More recently some of the financial analyses prepared by the big Accounting firms have been positive about the recent health of clubs in Scottish football. In many cases those involved still bear the scars of previous close calls and have developed keener business survival models. There is however still no effective safeguards in place on the part of the organisation responsible for the wellbeing of the game in Scotland to prevent further damage being done from future financial disasters. No lessons appear to have been learned. It leads to the inevitable concern that another disaster is always potentially around the corner until they get a handle on risk management and strong governance at clubs.

Scottish football runs without a strong profit motive. As a consequence most clubs run on thin margins to eek the best team out on the park that they can. It’s a model that’s prime for financial problems should things not go entirely to plan without the buffer of high levels of capitalisation to absorb losses. It is the SFA’s duty to protect such clubs from themselves as UEFA seeks to do on a European level. Because of statements like ‘not raking over old coals’, Scottish football and trust in its governance has failed to recover from the stigma of 2012. There is burning resentment, mistrust and a nasty edge fermenting. It is pervasive and wears no club colours. What is desperately needed is a programme designed to prevent the problems of the past recurring and that cannot be done without a full reckoning of what mistakes were made in the preceding period. The difficulties of Hearts, Dunfermline and Falkirk since then are a testament to a model still stuttering and failing.

What is in the past is done, but to continue doing the same thing and expecting different results is the very definition of insanity.

Part 2 of this series continues here.

Could have been a very good analysis, but it skirts the main issue as to why a club that is liquidated can go forward , with trophies and titles intact, suffering no Moral Hazard, apart from that done to our game?

To then pair that with a small sneer at the English Premiership, is to fail to grasp the extent of the football corruption that took place in 2012 and continues to this day.

LikeLike

It’s part 1 of a series and only deals with the circumstances under which it happened. It’s intended subsequent pieces deal with what happened after.

LikeLike

Perhaps so but it does contain the conclusion that we need to waive our regulations in order to learn more.

You need to own that point and justify it

LikeLike

You may be confusing this with a different article. Don’t think this particular one had such a conclusion. Instead that the rules weren’t fit to prevent disaster and aren’t sufficiently changed yet

LikeLike

You are correct.

I conflated this with the Res. 12 article which does contain such a conclusion and is supported by one of the readers of that article in the comment section.

Are these independent viewpoints by 2 different writers from the blog, or is this an agreed position? In short, do you disagree or not that an amnesty is necessary or helpful?

LikeLike

To clarify… indemnification against liability would mean against the financial implications of wrongdoing. Not that persons who acted wrongly get a free pass.

The Res 12 requisitioners necessarily had to raise this as a group of shareholders suffering financial loss to get things moving. One of the main reasons Rangers fans are against further scrutiny is the possibility of the new club being found liable under the five way for misdeeds of the old, which had very different people at the helm. Lost revenues, share price losses etc. This feeds the perception that Res 12 is a bunch of disgruntled Celtic shareholders upset about past events – a perception Regan played up at every opportunity. The SFA are also worried about financial liability when really the desired outcome is reform rather than money.

That is of course not what it is really about. It is about whether our Regulator acted fairly, honestly and within the intentions of UEFA in applying the FFP rules. It was they who tried to throw Rangers under the bus to protect themselves when ignoring the issue became no longer possible. If removing this financial threat allows the sort of openness that allows us to determine all the facts of the matter then that is an acceptable compromise to us – given our main focus is on having a better regulator going forward. It may not he to everyone. Shifting the focus onto regulatory issues in such a clear way would also go a long way to shift the incorrect perception of this being an anti-Rangers thing given there would be no repercussions on them and they could therefore get on board with cleaning up the regulator.

Cross party support for this is likely to be necessary to force the SFA’s hand as everyone has already seen the correspondence between Regan and Lawwell where one club itself could not force openness and accountability.

That’s our thinking and rationale.

LikeLike

Thank you for taking the time to write the article, but I fear that you’ve let yourself down with some of your comments. In the main article you state, “…an ill-fated 2012 campaign to insert the new Rangers into the second tier …”, and in one of your comments you say, “One of the main reasons Rangers fans are against further scrutiny is the possibility of the new club being found liable …” If your intention is to get “cross party support” for better regulation, why would you alienate the supporters of one of the two largest clubs in the country by using such incendiary language? Any reasonable Rangers fan reading this article would, upon reading these lines, conclude that you are just another btter supporter of another club who wants to further the petty anti-Rangers agenda that has been rife in Scottish football for years now. Ironically, you even address this in the same comment as the 2nd quotation that I highlight.

The depressing thing is, the actions of many Rangers fans since 2012 indicates a willingness to engage in regulatory reform and you could easily have won over these supporters (like those involved with Club 1872) had you not let your own bias and narrowmindedness taint an otherwise fine article.

I suggest you reflect on your choice of language when writing future articles on this subject and maybe also read the classic Dale Carnegie book, “How to win friends and influence people”.

LikeLike

Not being a fan of either club, it’s often hard to tell what fans of either will take offence to. Even now I’m not sure what is provocative about those statements or how any of it comes across as a desire to see Rangers punished. I simply don’t, only a full accounting for how the SFA acted. I suppose that could be my bias and narrow mindedness, though I suspect having no horse in the Glasgow race I’m in a better position to take an outside perspective. Yes the 2009 cup final hurt, but it’s in the past and beyond my current concerns. Don’t think you’d find many Falkirk fans harbouring serious grudges. In any case thanks for the comments and insults.

LikeLike

Some has just explained to me that’s it’s the word ‘new’ that is causing offence. No alternate deeper meaning intended other than a short handed explanation of events. As I said, don’t really get involved in new club/same club debate (other than a Hogmanay twitter discussion with some Celtic fans where I laid out how a ‘same club’ narrative would fit within the Rules). It it caused you offence it was neither intentional nor relevant to the central premise. I just don’t really pay that much attention to what upsets Celtic or Rangers fans.

LikeLike